Dementia is not choosy. It clings to the lives of diverse people, from the professional worker to the manual laborer, from the celebrity to the person living a private life.

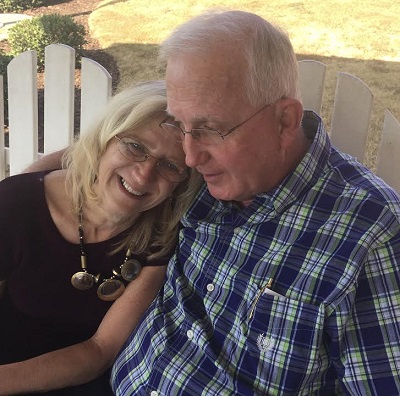

Such is the case for Georgia-based pharmacist, Robert Bowles, Jr. Schooled in pharmaceutical sciences, he owned and operated an independent pharmacy before health issues forced him to retire after 42 years.

Such is the case for Georgia-based pharmacist, Robert Bowles, Jr. Schooled in pharmaceutical sciences, he owned and operated an independent pharmacy before health issues forced him to retire after 42 years.

With all this knowledge and above average cognitive reserve, why was he diagnosed with dementia at only 64?

Five years ago, Bowles received a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with symptoms of Lewy body dementia. An oft-misdiagnosed disease, Lewy body dementia (LBD) was once described by a representative of the Lewy Body Dementia Association as walking like Parkinson’s and talking like Alzheimer’s.

Prior to this, he was a caregiver for his late father who lived with vascular dementia and his late mother, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Dementia steals and changes life plans

He began by experiencing symptoms that eight physicians over 18 months attributed first to stress due to overwork and then depression. Then he’d pass out due to a drop in blood pressure after standing up. His cardiologist couldn’t figure out what was going on and referred him to a neurologist who immediately diagnosed him with Parkinson’s. A month later, that neurologist revised his diagnosis to frontal temporal lobe dementia.

Ultimately, Bowles received a diagnosis of LBD in June of 2012. The explanation made sense given his symptoms of mild memory loss, Parkinson’s, hallucinations, dream acting, and nightmares. He felt a sense of closure and peace of mind, telling his family, “Everything will be okay.”

But it wasn’t. He began sleeping 16 to 20 hours a day and woke only to eat and use the bathroom. Sudden and extended periods of loud noises such as those during family gatherings were intolerable. The first time, he put both hands over his ears and screamed. “It was like a pinball machine being played in my brain. It pinged around amidst the dead cells until a live neuron could pick it up.” His doctors including one at the Mayo Clinic admitted, “That’s a very colorful way to say what’s going on.”

As hard as people without dementia (PWoDs) try to understand and learn from people like Robert, he says, “Unless you live with dementia, you can’t really understand the dynamics and the emotional affects.”

Caregiver Behaviors May Result in Need for Antipsychotic Medications

His interest in medications lead to our discussion of the use of antipsychotic medications to control behaviors.  He’s observed that caregivers unintentionally trigger adverse behaviors, which often lead to the prescribed use of antipsychotic medications. I asked if his caregiver and wife, Judy would be willing to share the example he began to give. He invited her and she explained to me, “If I interrupt him before he’s finished talking, it sets off a trigger. I can’t always tell when he’s finished talking because he takes long pauses between sentences. Also, he asks me a lot of questions and I sometimes don’t bother to answer him. In my mind, I’m wondering, do I have to answer everything he asks like, ‘Does that sound good?’ or ‘Is that okay?’”

He’s observed that caregivers unintentionally trigger adverse behaviors, which often lead to the prescribed use of antipsychotic medications. I asked if his caregiver and wife, Judy would be willing to share the example he began to give. He invited her and she explained to me, “If I interrupt him before he’s finished talking, it sets off a trigger. I can’t always tell when he’s finished talking because he takes long pauses between sentences. Also, he asks me a lot of questions and I sometimes don’t bother to answer him. In my mind, I’m wondering, do I have to answer everything he asks like, ‘Does that sound good?’ or ‘Is that okay?’”

It’s challenging from both perspectives and I offer her words of comfort. “It’s a tradeoff between your exhaustion as a caregiver versus his need to feel understood and respected.”

“Exactly! You hit the nail on the head,” she replied.

Robert explained that he asks her questions to engage her in decisions. During their 46-year marriage, he’s been the key decision maker. Early on in their marriage, Judy was hospitalized for a week or more due to complications with lupus. Robert took care of their three children. Today, he wants to involve her as they work together to make plans for their future.

“Retrieval processing becomes a trigger for me, sometimes. My memory is grossly intact. In LBD, memory doesn’t typically decline as fast as it does in Alzheimer’s. When my train of thought jumps the track and people try to help too quickly, I feel like I’m put into a box I can’t get out of and then I go totally blank.”

As we caregivers learn more about how our actions impact those we care for, we can decrease the need for antipsychotic medications. Should the need arise, Robert would prefer to use THC, a key ingredient in marijuana, rather than risk the possible significant side effects of antipsychotic medications.

LBD Psychiatric Effect of Hallucinations

People living with LBD also experience hallucinations, especially at night. Robert recalls waking up sore from dream acting (kicking all night). Another time, he watched (hallucinated) two people conversing, “We got his personal info and we got his medical records and we’re going to get his financial records.” He said, “I woke up with my right fist slamming the palm of my left hand thinking I was talking on the phone and slamming the phone, instead.”

Faith is strong

Several months after the LBD diagnosis, he says, “I felt like a convicted murderer. The physician entered the charges, and the jury found me guilty. The judge issued the death sentence without appeal.”

Robert’s faith has been his foundation and helped him the most while living with LBD. “One morning, I awoke and came into my [home] office. I cried out to God, I cannot take this disease anymore. Please take me home. (I’ve never done this before to this extent or after.) And then I realized, Oh God, you’re not through with me yet! It was as if the Lord was sitting next to me, saying, ‘Just as you loved your patients in the pharmacy, you cared for them, you educated them, and you gave them hope; I have a much bigger mission for you.’”

He told Judy what happened later that morning, and enlisted her help in a massive fundraiser for the Lewy Body Dementia Association. That September morning of 2013 marked the beginning of his advocacy.

Today, he says he’s doing better than when he was diagnosed. He offers ASAP as a guiding model to live well with dementia. ACCEPT your diagnosis. Maintain equal or greater SOCIALIZATION than before the diagnosis. Have a positive ATTITUDE. Find your PURPOSE in life.

Robert Bowles with Laurie Sherrer from Pennsylvania who lives with Alzheimer’s and frontal temporal lobe dementia. “We met through Dementia Mentors three years ago, and have supported each other, virtually (online). While visiting her cousin and his mother in Atlanta, Laurie suggested we meet. Photo taken by Judy Bowles, Robert’s wife.

He spends six to eight hours, daily engaged in dementia advocacy. On his website, LBD Living Beyond Diagnosis, he writes, “Individuals with dementia can still do a lot of things.” Robert serves on the Board of Directors and the Advisory Council of the Dementia Action Alliance (DAA). “DAA’s foundation of listening to the person living with dementia and person-centered care fit like a glove” and he adds “their passion mirrored my advocacy mission.” He’s also active on several Facebook pages and as a Dementia Mentor, participating in webinars and virtual Memory Cafes.

In an interview for a U.S. News Health article: When Do We Stop Listening? in 2015, he said, “We need to keep pushing to raise awareness. Think of it, why does someone not visit a person with dementia? They’re afraid. They don’t [feel they know how to talk with or interact with a person with dementia.] If we reduce the stigma, we’ll see the culture change and the lives of care partners and persons with dementia will be better.”

For more about Robert Bowles, visit his website at Lewy Body Dementia Living Beyond Diagnosis

The Caregivers Voice Article featuring Robert and Judy Bowles and their experience living with LBD was least to say most inspiring. I know them personally and have had the privilege of working with them the last few years in promoting dementia awareness. I have been away for the past few months and my passion had diminished somewhat. But, after reading this article, Robert’s compassion for people with dementia and his determination to achieve what God has inspired him to do has reinforced to me the urgent need for getting the word out. Not only for those with dementia, but for the loving caregivers who face different challenges everyday. (I was one of those caregivers without the knowledge of how to adequately care for my mother with LBD.)

The author, Brenda Avadian, really did a great service by featuring Robert’s story. It was written so well and really captured his experiences in his journey and his commitment to obeying what God has commissioned him to achieve. It reopened my eyes, and I pray that many living with dementia will be advised of Robert’s story, thus helping them realize that there is “life after diagnosis.” I also pray that many caregivers read the article to reap the benefit of Judy’s many challenges and experiences as Robert’s loving wife and caregiver.

Robert and Judy are special people, and this article captured just how special they both are.

God Bless Robert and Judy. And, God bless all people traveling the journey with dementia and the caregivers helping them along the way.

Elaine Harrison

Sent from my iPhone

Elaine, thank you for your encouraging words. Comments like yours are the nourishment we (caregivers, people with dementia, and The Caregiver’s Voice) need to keep going. 🙂

Great article Robert and great to hear a little of Judy’s reactions to your dementia! You are lucky to have her!

It is unfortunate that the AD and dementia industry now has a Trump person who has never uttered one word about dementia. We lack one major loud voice to be our national spokesperson. The AA has only to offer Run for the Cure. Money first, false promises second, sure failure. WHO projection 2050 seems the only logical time frame, those with terminal will pass as we wait for an early onset miracle that keeps drifting further into the clouds. As a professional I am terribly disturbed that the world working so hard has not produced at least the early remission to stem the progression.

I agree with you, Norman.

And yet, many voices give us a better perspective than the limited view we had as recent as 20 years ago.

Still, as you point out, we can do much better in the areas of research and I’ll add, caregiving.

Having been in this field for 21 years, I find too many trying to reinvent the same path (silo mentality) instead of reaching out to work together.

When we unite our efforts, we will be stronger and take greater strides.

Yet, funding doesn’t seem to work this way.

Instead, we remain competitive.

I think the argument that competition fosters creativity is passé.

And people like Robert Bowles and others featured in this VOICES with Dementia column and Dementia Mentors are making strides in making people aware that one can live a productive life with dementia.

Again, thank you, Norman for your comment.