There are over five million Americans living with Alzheimer’s disease today and it is the only disease in the top 10 causes of death that cannot be prevented, slowed, or cured. Alzheimer’s is unique, as it’s considered a family disease, impacting not only those with the disease, but also their caregivers – totaling more than 15 million Americans.

There are over five million Americans living with Alzheimer’s disease today and it is the only disease in the top 10 causes of death that cannot be prevented, slowed, or cured. Alzheimer’s is unique, as it’s considered a family disease, impacting not only those with the disease, but also their caregivers – totaling more than 15 million Americans.

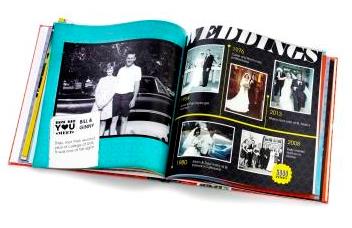

Because people with Alzheimer’s may retain their long-term memories, especially during the earlier stages of the disease, research supports the use of reminiscence – the discussion of past activities, events and experiences with another person, usually with the aid of tangible prompts such as photographs. Reminiscence can promote feelings of comfort and connection while reducing feelings of isolation and withdrawal. Studies also find that caregivers who participate in reminiscence report lower strain.

This month, aided by experts at the Alzheimer’s Association, Shutterfly drew on its strong heritage in helping families share life’s joy to launch a new resource page that offers 10 tips for putting together meaningful photo books for people with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. These tips are meant to serve as a practical guide for engaging those with Alzheimer’s disease and using photos as tangible prompts for conversation:

- Place photos in chronological order.

Photo books can be great tools for showing someone’s life history or story. Start your photo book at the beginning of the person’s life and lead up to the present day. Organize the book around key moments and concentrate on happy occasions to assist with engagement. Also, keep the design simple, with one or two pictures per page, so the photos are easy to focus on. - Show relationships.

To help spark recognition of family members, dedicate a section to each person. Choose photos that include the person with the family member from different life stages and place them in chronological order.

- Select meaningful moments.

Be sure to include photos that reflect the person’s meaningful life moments and depict his/her favorite hobbies or activities, such as weddings, graduations, and vacations. - Make it an activity.

Work with the individual as appropriate to create the book, and share memories and conversation as you put it together. - Engage in conversation.

Ask open-ended questions about the people or events in the photo. How were you feeling in that picture? Tell me about your brother. What are some of your favorite childhood stories? Tell me more about this picture. The answers are less important than the conversation and engagement. - Share your own memories.

As part of the conversation, share your memories and feelings when looking at the pictures. Answer some of the same questions you’re asking the person with Alzheimer’s. - Connect, don’t correct.

This is more about making a connection and sharing memories. Focus on connecting with the person, not correcting him/her. - Revisit frequently.

Take the time to frequently revisit memories using the photos. Do what works best for the individual. It may be daily or weekly, depending on the person. - Mix it up.

Don’t discuss the same set of photos week after week. To help keep it fresh and interesting, discuss various parts of the book with different people and events on a regular basis. - Move at a comfortable pace.

Follow cues from the individual to gauge his/her interest level and determine how much time to spend per photo. Spend more time on the ones that spark interest or conversation and move on if they do not.

To learn more about this partnership, please visit the Shutterfly-Alzheimer’s Association website.

ABOUT the AUTHORS

Lara Hoyem serves as the Director of Photo books for Shutterfly. She began using Shutterfly in 2000 with the birth of the first of her two daughters and today enjoys taking photos while traveling. She earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in human biology from Stanford.

Sam Fazio, PhD serves as Director of Special Projects for the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Fazio has worked for the Alzheimer’s Association since 1994 in education and training and now in constituent services. He received his doctorate in developmental psychology from Loyola University Chicago.