Guest Article by Suzanne Marriott

Growing Up

My father was a farmer. He was often seen sitting on his dust-covered tractor, the four corners of a red bandana knotted to form a hat to protect his head from the sun, and a pack of Lucky Strikes in the left breast pocket of his sweat-stained blue work shirt. “Take me for a ride on the tractor,” I’d plead. Oh, how I loved climbing up on the toolbox to ride with him—just for a bit. For my father that old tractor was all about work, but for me it was an alluring adventure and a brief glimpse into another world.

On summer afternoons, I’d climb into his Ford pickup and we’d ride into town. First, we’d stop at Ranch Supply for a chat with the owner and to pick up a bag of Purina Chow for my dog. Then across the railroad tracks to say, “Hi” to my uncle and aunt who owned the local hardware store. Next door was the ice creamery where we’d stop for sundaes.

In the evenings, I’d climb in the pickup again, this time with my dog, and off we’d go to check the water that irrigated the cherry orchard. I loved those warm evenings and the soft gurgle of water as it filled the ditchers and replenished the soil.

Gifts From My Father

My father taught me many things. He loved animals and encouraged me in the care of my childhood pets. His dedication to nurturing his crops was a testament to his love of nature and all living things. Above all, he cared for me with compassion and unconditional love.

A time came when my hard-working father could no longer put in the long hours of running a farm. The times of drenching crops with deadly spray took its toll and neurological problems sapped his strength. Most often it was parathion in the tank, a vile, insidious [pesticide, the use of which is restricted today]. I can still remember the acrid, choking smell of the spray material that was stored in one of our white-washed sheds. I didn’t go in there often: I was cautioned to stay out.

Perhaps it was the stuff he sprayed with that caused his slowly creeping dementia. Sometimes he became angry, so unlike the loving father he always had been. I remember one time when I, now an adult, came home for a visit. After one of his outbursts I said, “It’s all right, Daddy, you weren’t yourself.” Looking up at me, confused, he asked, “Who was I?”

When my father became ill, it was my turn to care for him. That took many forms: from handling the bills to spending quiet time, just being together. The hardest part was called “spending down” when I paid for home health care for him until he qualified for Medicaid and entered a nursing home.

I was one of the lucky ones, for a smile of recognition never failed to appear on his face when I visited. He passed away quietly in a hospital, his work done but his love enduring.

My Husband

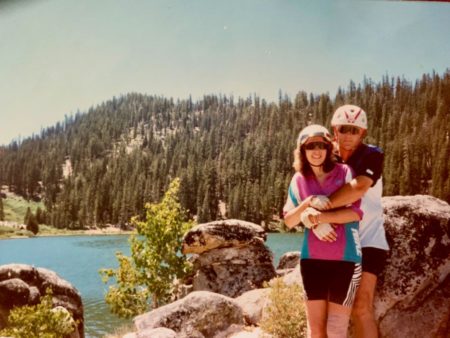

My husband, Michael, and I were an active couple. We loved our backpacking adventures and we excelled at mountain-biking, traversing the many trails near our home and mastering the challenging Flume Trail above Lake Tahoe. Yet all too soon those adventures ended when Michael was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. His decline was gradual, from dragging one leg while hiking, to relying on his two hiking poles, to becoming wheelchair bound.

Michael hadn’t always been sympathetic to my father’s condition. While we were visiting one day, my father came back from the grocery store; embarrassed and discouraged. He told us he had fallen down in the aisle. Michael had seen my father maneuver around his house very well, and later told me that he didn’t believe my father had fallen in the store.

Years later, dependent on his hiking poles and haven fallen himself, Michael realized the difference between getting around familiar surroundings and trying to maneuver in public places. “I wish I had gotten to know Bob better,” he told me, referring to my father. “I understand what he was going through.” Situations like this have taught my husband compassion, for others and, increasingly, for himself.

Like my father, my husband’s cognitive functions declined. I remember watching the memory test a doctor administered for Michael to qualify for disability status. At the beginning of the exam, the doctor gave Michael three items to remember. At the end, Michael could remember only two. I squirmed inside as I watched him grope for the answer and, finally, realize he just couldn’t remember.

Over the years that Michael suffered from MS, he was in and out of hospitals many times, often experiencing severe memory loss. In one instance he questioned me, trying to determine acceptable behavior in this strange, new world.

“Is it all right to talk to the nurses? Is it all right to ask them to do things for me?”

“Yes, of course,” I reassured him.

“Is it all right to ask one to get in bed with me?” This question was asked seriously, in the same innocent voice.

“No,” I had to inform him, and I tried not to laugh. He nodded, calmly absorbing this important information.

Lessons Learned

Among the lessons I learned from my father was how to be his caregiver. During the years my husband had MS, my caregiving tasks increased a hundred-fold. I learned to accomplish things I never thought possible, like changing a Foley catheter and administering IV medications. Throughout it all, most important was learning compassion, for without it I would have been doing things for my father and my husband, but not truly caring for them.

I’m glad I was there for my father and my husband. My hope is that my experiences will inspire you, caregiver, to share in caring companionship with your loved one as you find your way along your caregiving journey.

Suzanne Marriott holds an MS in Education and an MA in Transpersonal Psychology. Her memoir, Watching for Dragonflies: A Caregiver’s Transformative Journey [available June 2023], describes her psychological and spiritual growth through caregiving. She lives in a cohousing community in the Sierra foothills and enjoys spending time in the natural beauty that surrounds her.