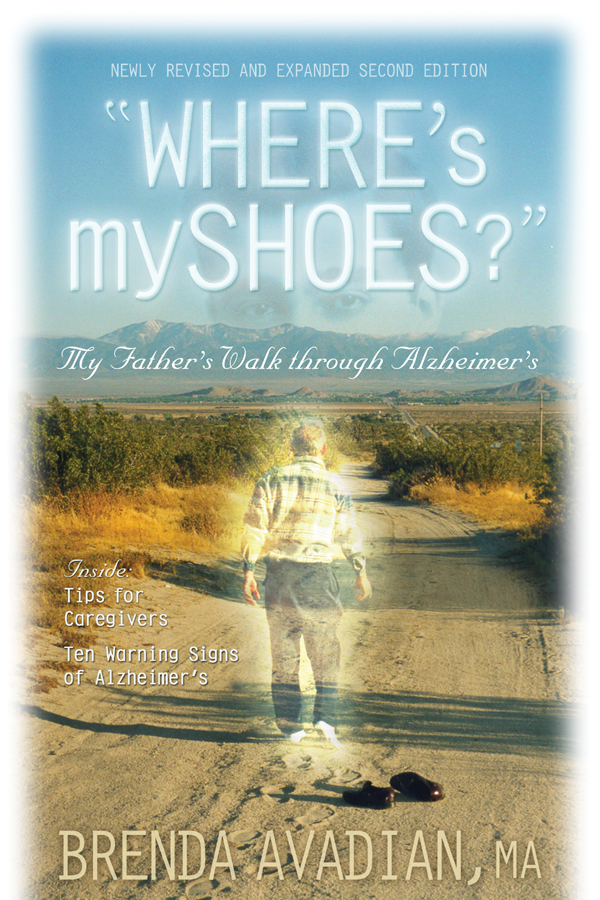

Fifteen years ago this month, my husband and I were visiting my father in Wisconsin with the idea of placing him in an assisted living community to better help him live with dementia. We called him Mardig (Armenian for Martin). As days passed, we grew overwhelmed trying to make sense of years of disorganized paperwork. We persuaded him to visit us in California. Below are excerpts from “Where’s my shoes?” My Father’s Walk through Alzheimer’s

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 4

Our Lives Take an Unexpected Turn

David and I spent the next few days sorting through Mardig’s papers. Mardig enjoyed our genuine interest and began reflecting on events from his earlier years. His past was a mystery to us since he did not talk about his family. Old family conflicts and misunderstandings had kept his side of the family away from ours. His mother lived her final years with his half-brother in the Chicago area. After the relationship soured between my parents and my aunt and uncle, we no longer visited them. Regrettably, my grandmother died before I had the opportunity to learn about my father’s childhood.

While looking through one of the file cabinet drawers, I came upon a tattered oversized envelope. Inside was a worn brown composition book dated 1929. It was Mardig’s composition book from an adult evening class to improve his English. Inside were pages filled with selected events from his childhood. I focused on an autobiographical assignment.

At the tender age of five, Mardig and his mother narrowly missed the first genocide of the twentieth century. They left Van (in Turkey) just in time for the relative safety of Constantinople (now Istanbul).

I showed my father his brown composition book and asked him to read the autobiography and he recounted some of the stories of when he and a friend went swimming in the sea. David asked him about the journey coming to America in 1920 on the steamship Pannonia from Patras, a port in Greece. He chuckled and recounted a few stories of running around the ship and scaring his mom who was trying to keep from being seasick.

![]()

David and I pored through Mardig’s papers. It was nearly impossible to determine what was important and what was not. We had to leaf through it all, one page at a time, being careful not to overlook something—like a $1,000 U.S. Savings Bond tucked between two sheets of scrap paper or hiding in a one-and-a-half foot pile of newspapers my brother threatened to throw away. Despite mustering some energy after discovering more details of my family history, this overwhelming task soon exhausted David and me.

I scraped off the rubber bands and unfolded a letter-sized sheet that was protecting a stack of cards. When I turned them over to look at the front side, in the upper right corner I saw “1,000” . . . twenty-eight thousand dollars in U.S. Savings Bonds.

After lunch one day, having washed the dishes and wiped off the table, I returned to the sunroom. I watched my father, who was hunched over paperwork in his preferred place of work and rest (there was also a bed in the room). Five arched windows lined three brick walls. Once framed by silk-lined drapes tied back to let the sun stream in, these same drapes, now rotted from fifty years of sun damage, were closed. A single light bulb on Mardig’s desk illuminated one corner of this otherwise dark room.

I walked closer to look over his shoulder. He was organizing his bills. I sat in a chair by a bookshelf in the living room, only a few feet away from where he was working. Soon, I grew bored and turned my attention to the books in this last of the three built-in dark oak bookshelves that lined the north wall of the living room. Some were my father’s German-language books from his bachelor years; others were reference books he used for his work as a machinist. Two hardcover books covered with brown paper bags grabbed my attention. I tried to decipher the rubber-stamped letters on their spines. Reaching out, I pulled one off the bookshelf. A little package fell onto the floor. After looking quickly at the book, an engineering manual of interest to my father, brother, or David, I placed it back and reached down for the package.

Three dried-out rubber bands bound an eight-and-a-half by three-and-a-half-inch package. I scraped off the rubber bands and unfolded a letter-sized sheet that was protecting a stack of cards. When I turned them over to look at the front side, in the upper right corner I saw “1,000” and on the upper left side “1,000.” I looked at the card more carefully and read, “Series E.” It finally dawned on me—it was a thousand dollar U.S. Savings Bond! I lifted a corner of the first bond to look at the second card and saw the same writing. I lifted the second bond and saw yet another “1,000.” I fanned them out like a deck of playing cards and counted, four thousand, five thousand, six . . . fifteen thousand . . . twenty thousand . . . twenty-five thousand . . . twenty-eight thousand dollars in U.S. Savings Bonds. My heart fluttered!

“Mardig, look what I found!”

![]()

Shortly before we were to return to California, my father agreed to visit. I bought a one-way plane ticket.

What am I doing? Is this really a smart thing to do, bringing my father to California? Am I doing something wrong? The wretched fear of the youngest child, whose parents tried to make her behave more like her older siblings, cast a long shadow. Even though my sister, brother, and I were not communicating, this was also their father I was relocating.

My husband’s and my lives were about to take a life-changing turn.

Brenda Avadian, MA

Alzheimer’s / Dementia Caregiver, Expert Spokesperson, Coach, and Author