Every now and then, I step away from what I have scheduled for the day to catch up with informative yet touching caregiving articles that have been sent to The Caregiver’s Voice. Such is the case with this Harvard Magazine article sent to us in June.

Professor Arthur Kleinman, a caregiver to his wife, writes a compelling article entitled, On Caregiving in the July-August issue. He draws heavily on his experience as a psychiatrist and anthropologist as he explores first-hand the moral dilemmas of caregiving during his forty-four year career.

His story begins as a visiting medical student at a London teaching hospital in 1966 where he had the insight to challenge his professor’s primarily scientific approach with a more human view of people’s concerns with how to live their lives following a major health diagnosis.

“To prepare for a career of caregiving, medical students and young doctors clearly require something besides scientific and technological training that, even as it enables the physician as a technical expert, risks disabling her or him as a caregiver.”

I agree with Kleinman. Fortunately, the UCLA Medical School has (had?) the wisdom to provide this aspect of training to resident doctors. At least, they did while inviting me to help their doctors become aware of the family caregiver’s perspective.

But what about the millions of caregivers worldwide who provide care?

As a caregiver to his wife living with Alzheimer’s, Dr. Kleinman addresses the needs faced by professional and family caregivers.

As a medical anthropologist he explores how caregiving looks through the eyes of an economist (a burden) or a psychologist (coping). Kleinman views caregiving as an “existential quality of what it is to be a human being.”

“I believe that what doctors need to be helped to master is the art of acknowledging and affirming the patient as a suffering human being; … conversing with and supporting patients … where the emphasis is on what really matters to the patient and his or her intimates.”

Imagine how much we could improve medical care if our doctors had the time to follow this prescription.

“And because caregiving is so tiring, and emotionally draining, effective caregiving requires that caregivers themselves receive practical and emotional support.”

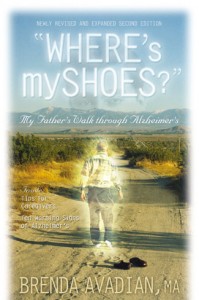

I laughed when he wrote about his wife asking about her shoes? Unlike my father’s dementia which took away his use of correct grammar as he repeated, “Where’s my shoes?” seventy-year-old Joan asks her sixty-nine-year-old husband, “Where are my shoes?” while her brain amazingly does not register the eighteen pairs situated on the rack. But I cannot laugh for long, because her question frustrates her well-meaning husband of forty-five years as it does so many of us caregivers. Sadly, she senses his frustration and cries out for help: “Should I kill myself?”

I laughed when he wrote about his wife asking about her shoes? Unlike my father’s dementia which took away his use of correct grammar as he repeated, “Where’s my shoes?” seventy-year-old Joan asks her sixty-nine-year-old husband, “Where are my shoes?” while her brain amazingly does not register the eighteen pairs situated on the rack. But I cannot laugh for long, because her question frustrates her well-meaning husband of forty-five years as it does so many of us caregivers. Sadly, she senses his frustration and cries out for help: “Should I kill myself?”

“[Caregiving] is a practice of empathic imagination, responsibility, witnessing, and solidarity with those in great need. It is a moral practice that makes caregivers, and at times even the care-receivers, more present and thereby fully human.”

Please don’t take as long to read this article as I did. Take time to read this thought-provoking and inspiring piece by clicking on On Caregiving – Harvard Magazine July-August, 2010

For a related article, Caregiving: The odyssey of becoming more human scroll to Kleinman’s biography at the bottom for the link. I would have included the live link here; however, permission was granted by the The Lancet for readers of the Harvard Magazine article.

Arthur Kleinman is the Rabb professor of anthropology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, professor of both medical anthropology and psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, and Fung director of the Harvard University Asia Center.